儿童睡眠呼吸障碍 (sleep disordered breathing, SDB) 发病率较高,其中阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停低通气综合征 (obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome,OSAHS) 是该疾病中对儿童身体健康危害最大的一种。多数儿童SDB主要是以轻到中度的OSAHS与单纯打鼾为主,主要的临床表现为:白天多动、异常行为与认知功能障碍[1]。OSAHS儿童的主要病因有:① 扁桃体、腺样体肥大;② 神经肌肉异常;③ 先天性因素;④ 其他,如肥胖、过敏性鼻炎等。有新兴证据表明,25羟维生素D[25(OH) D]具有免疫调节功能[2]。有学者推测25(OH) D可能在OSAHS的发病中起作用,循环中低水平的25(OH) D会增加上呼吸感染,引起扁桃体肥大及鼻炎[3-5]。低水平25(OH) D可导致继发性甲状旁腺激素水平升高,钙离子内流入脂肪细胞,致脂质生成增多,脂肪分解减少[6-7],从而引发肥胖。低水平25(OH) D导致较差的肌肉骨骼功能,不足以支撑上气道从而加重睡眠呼吸暂停。国内外不断有研究从代谢的角度探索可以反映OSAHS患者严重程度的指标,但对儿童的研究相对缺乏。我们通过检测儿童血清25(OH) D水平,并与儿童OSAHS各项睡眠监测指标、血脂指标及认知行为异常进行相关性分析,期望可以从患儿血液代谢角度指导此类患儿的临床诊疗。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料选取2016年7月至2016年10月间因睡眠时打鼾就诊于山东大学齐鲁医院耳鼻咽喉科并住院治疗的3~12岁儿童69例,行整夜睡眠监测,依据2014年国际睡眠障碍分类标准第三版[8],分为以下两组:OSAHS组47例 (男32例,女15例),单纯鼾症组22例 (男10例,女12例)。采取空腹血测定血清甘油三酯 (TG)、总胆固醇 (TC)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇 (HDL-C)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇 (LDL-C) 水平,并采用Conners父母症状问卷从品行问题、学习问题、心身障碍、焦虑、冲动-多动、多动指数方面评估各组儿童行为认知问题。对照组选取同季度、同年龄段于儿科门诊查体的70例健康儿童 (排除睡眠呼吸障碍以及其他心肺疾病),其中男45例,女25例,各组间年龄、性别差异无统计学意义。所有患者并排除以下:① 曾行腺样体切除术或扁桃体切除术;② 服用可能影响25(OH) D水平的药物和食物,如钙剂、维生素D类药物、抗癫痫药、糖皮质激素等;③ 伴有代谢性疾病,如糖尿病、胰岛素抵抗、高脂血症、高血压、心脑血管疾病、甲状腺疾患、甲状旁腺疾患、骨质疏松症及骨折等病史;④ 合并急慢性感染、鼻息肉、鼻腔肿物、后鼻孔闭锁等疾病;⑤ 合并小下颌畸形、短下颌、巨舌症,以及各种以颌面部发育异常为主的综合征;⑥ 伴有心肺疾病、遗传疾病及胃肠道疾病等;⑦ 伴有其他神经系统、神经肌肉性疾病及精神疾病。

1.2 研究方法所有受试者均记录性别、年龄、身高、体质量及服用药物史。睡眠监测采用睡眠呼吸初筛仪 (北京德海尔医疗科技有限公司,DHR998),睡眠时间至少7 h。通过采集PPG信号、血氧、心率、鼾声、体位信号,由计算机自动分析得到低通气指数 (apnea hypopnea index, AHI)、最低血氧饱和度 (The Lowest of Oxygen Saturation, LSaO2) 等指标。根据儿童阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停低通气综合征诊疗指南草案 (乌鲁木齐)[9],对儿童OSAHS严重程度及低氧血症严重程度进行分级:轻度AHI 5~10,LSaO2 0.85~0.91;中度AHI 11~20,LSaO2 0.75~0.84;重度AHI > 20,LSaO2 < 0.75。睡眠监测次日清晨空腹时抽取外周静脉血约7 mL,立即送至本院中心检验科,应用罗氏生化免疫分析组合仪测定TG、TC、HDL-C、LDL-C,并用化学发光免疫测定法测定外周血清25(OH) D[包括25(OH) D2、25(OH) D3]的水平。按血清25(OH) D水平判断维生素D (VitD) 营养状况, 目前国际比较公认的评判标准[10]为: ① VitD严重缺乏:血清25(OH) D水平≤10 ng/mL; ② VitD缺乏:10 ng/mL<25(OH) D水平≤20 ng/mL; ③ VitD不足:20 ng/mL<25(OH) D水平<30 ng/mL; ④ VitD充足: 25(OH) D水平≥30 ng/mL;⑤ VitD过量:25(OH) D水平>100 ng/mL。维生素不足和缺乏都被归为低维生素D浓度。

1.3 统计学处理采用统计软件SPSS 22.0,年龄不符合正态分布以中位数[25分位数, 75分位数](M[P25, P75]) 的形式表示,差异比较用Kruskal-Wallis H检验。体质量指数 (body mass index, BMI)、25(OH) D符合正态分布,多组间差异比较采用单因素方差分析,组间两两比较采用Bonferroni法,计数资料采取χ2检验。单纯鼾症组和OSAHS组间TC、HDL-C、LDL-C比较用独立样本t检验,TG用Mann-Whitney U秩和检验。两指标间的相关性分析采用Pearson相关分析、Spearman秩相关分析。所有统计检验采用双尾,检验水准α=0.05,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 三组儿童生理指标比较本研究中对照组儿童70例,69例打鼾症状儿童诊断为OSAHS 47例,诊断为单纯鼾症22例。OSAHS组、单纯鼾症组、对照组儿童年龄、性别分布比较差异均无统计学意义 (χ2=3.125,P=0.210;χ2=3.451,P=0.178),体质量指数 (body mass index,BMI) 差异有统计学意义 (F=3.674,P=0.028)。组间两两比较,OSAHS组儿童BMI大于单纯鼾症组,差异有统计学意义 (P=0.035)。OSAHS组、单纯鼾症组及对照组儿童25(OH) D质量浓度组间差异有统计学意义 (F=9.458,P < 0.001)。进一步做两两比较 (Bonferroni法),OSAHS组25(OH) D水平低于对照组,差异有统计学意义 (P < 0.001), 单纯鼾症组与对照组及OSAHS组25(OH) D水平差异均无统计学意义 (P值均 > 0.05)。见表 1。

| 表 1 3组儿童基本资料和血清25(OH) D比较 Table 1 The demographic characteristics and 25(OH) D levels of PS, OSAHS and control groups |

根据《儿科学》(7版) 中制定的儿童单纯性肥胖诊断标准[11], 将所有受试者分为a:肥胖 (+) OSA (+), b:肥胖 (-) OSA (+), c:肥胖 (+) OSA (-), d:肥胖 (-) OSA (-) 四组。差异用Kruskal-Wallis H检验,组间两两比较采用Bonferroni法。肥胖 (-) 儿童中,OSA (+) 儿童25(OH) D水平明显低于OSA (-) 儿童,差异有统计学意义 (P=0.001)。OSA (+) 儿童中,肥胖 (+) 儿童与肥胖 (-) 儿童25(OH) D水平差异无统计学意义 (P=0.566)。见表 2。

| 表 2 不同肥胖类型儿童血清25(OH) D水平的比较 Table 2 The serum 25(OH) D levels of 139 obese and non-obese children with and without OSAHS |

比较单纯鼾症组和OSAHS组儿童血脂指标 (TG、TC、HDL-C、LDL-C), TC、HDL-C、LDL-C满足正态分布,两组比较用独立样本t检验,TG为偏态分布,两组比较用Mann-Whitney U秩和检验。两组之间血脂指标差异无统计学意义 (P值均 > 0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 单纯鼾症组和OSAHS组儿童血脂指标比较 Table 3 Comparison of lipid indexes between PS group and OSAHS group |

根据Conners父母用量表 (1978) 因子常模,比较单纯鼾症组儿童和OSAHS组儿童关于Conners父母症状问卷的品行问题、学习问题、心身障碍、焦虑、冲动-多动及多动指数的差别,见表 4。对两组存在Conners症状问题的例数行χ2检验,两组之间无统计学差异 (P=均 > 0.05)。

| 表 4 单纯鼾症组和OSAHS组儿童Conners父母症状问卷指标比较[n(%)] Table 4 Comparison of Conners PSQ results between PS group and OSAHS group[n(%)] |

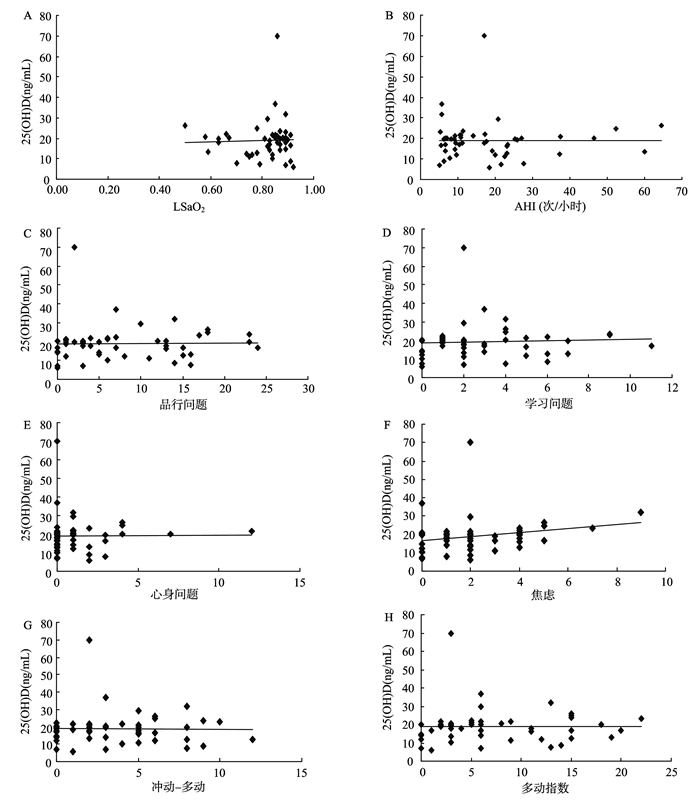

用Spearman秩相关系数分析方法,OSAHS组25(OH) D水平与焦虑呈正相关 (r=0.337, P=0.020),与LSaO2、AHI、品行问题、学习问题、心身障碍、冲动-多动、多动指数、TG均未发现明显相关性 (r值均 < 0.5,P值均 > 0.05)。用Pearson相关分析,OSAHS组25(OH) D水平与TC、HDL、LDL无明显相关性 (r值均 < 0.5,P值均 > 0.05)。见图 1。

|

图 1 25(OH) D与LSaO2、AHI、品行问题、学习问题、心身障碍、焦虑、冲动-多动、多动指数、TG、TC、HDL-C、LDL-C相关性散点图 A: 25(OH) D与LSaO2无相关性 (r=0.066,P=0.657); B: 25(OH) D与AHI无相关性 (r=-0.048,P=0.751); C: 25(OH) D与品行问题无相关性 (r=0.023,P=0.879); D: 25(OH) D与学习问题无相关性 (r=0.023,P=0.879); E: 25(OH) D与心身障碍无相关性 (r=-0.002,P=0.987); F: 25(OH) D与焦虑有相关性 (r=0.337,P=0.020); G: 25(OH) D与冲动-多动无相关性 (r=0.081,P=0.587); H: 25(OH) D与多动指数无相关性 (r=-0.015,P=0.918); I: 25(OH) D与TG无相关性 (r=-0.202,P=0.173); J:25(OH) D与TC无相关性 (r=0.040,P=0.791); K: 25(OH) D与HDL无相关性 (r=0.100,P=0.506); L: 25(OH) D与LDL无相关性 (r=-0.013,P=0.929)。 Figure 1 Scatterplots of serum 25(OH) D levels vs. lowest SpO2, obstructive AHI, Conners PSQ, TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C in OSAHS group (from A to L) A: No significant association between 25(OH) D and the lowest of oxygen saturation (r=0.066, P=0.657); B: No significant association between 25(OH) D and apnea hypopnea index (r=-0.048, P=0.751); C: No significant association between 25(OH) D and conduct problems (r=0.023, P=0.879); D: No significant association between 25(OH) D and learning problems (r=0.023, P=0.879); E: No significant association between 25(OH) D and psychosomatic disorders (r=-0.002, P=0.987); F: Significant association between 25(OH) D and anxiety (r=0.337, P=0.020); G: No significant association between 25(OH) D and impulsivity-hyperactivity (r=0.081, P=0.587); H: No significant association between 25(OH) D and hyperactivity index (r=-0.015, P=0.918); I: No significant association between 25(OH) D and triglycerides (r=-0.202, P=0.173); J: No significant association between 25(OH) D and the total cholesterol (r=0.040, P=0.791); K: No significant association between 25(OH) D and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (r=0.100, P=0.506); L: No significant association between 25(OH) D and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (r=-0.013, P=0.929). |

儿童OSAHS是一种儿童期较为常见的疾病,长期出现睡眠呼吸暂停和低通气将可能造成患儿的生长发育落后、心功能改变、传导性耳聋及颜面发育畸形。扁桃体肥大和腺样体肥大是导致儿童鼻咽部及口咽部狭窄最常见的原因。

维生素D (VitD) 在人体中有广泛的生理作用,为生长发育所必需。人体所需的VitD主要由皮肤经紫外线照射合成。VitD主要有两种形式:VitD2和VitD3。VitD首先在肝细胞线粒体内进行第一次羟化,生成25(OH) D;在肾脏第二次羟化,生成1,25(OH)2D。1,25(OH)2D是体内VitD主要的活性形式。25(OH) D是VitD代谢主要的中间产物,其半衰期长,不受甲状旁腺激素 (PTH)、血钙、血磷等的影响,能反映VitD的综合代谢水平,是评价机体VitD营养状况的最佳指标。VitD的经典作用除了调节机体的钙、磷代谢平衡[12],还有更广泛而重要的生理功能,如保护中枢神经系统[13-14]、调节免疫、抗肿瘤[15]和防治代谢综合征[16]等。本研究发现,正常健康儿童、单纯鼾症儿童与OSAHS儿童25(OH) D水平呈阶梯式下降,其中OSAHS儿童血清25(OH) D水平明显低于正常儿童25(OH) D水平,差异有统计学意义,这与Gominak等[17]的研究一致。

有研究表明,扁桃体肥大与低水平VitD有关[4],而扁桃体肥大是儿童OSAHS的主要病因之一。其机制可能为:VitD能加强先天性免疫,即抗菌活性,降低获得性免疫,即抗原表达,T、B淋巴细胞活性等,起到保护作用[18]。低水平的VitD可使外周T淋巴细胞总数及Th细胞百分比明显下降,引起细胞免疫和体液免疫功能下降[19], 从而导致上气道免疫调节功能失调,引起炎症反应,增加上呼吸道感染,从而引起扁桃体肥大和慢性鼻炎[20-21]。而补充维生素D可降低儿童上呼吸道感染的风险[22]。除此之外,VitD能够在体外阻断丝裂原诱导的扁桃体组织增殖[23]。

研究发现,低水平VitD可导致继发性甲状旁腺激素水平升高,钙离子内流入脂肪细胞,致脂质生成增多,脂肪分解减少[6-7]。无论在体内还是体外,过氧化物酶体增殖体激活受体γ(PPARγ) 脂质形成都是必需的。VitD还可以抑制PPARγ的表达来抑制前脂肪细胞的分化[24]。而肥胖儿童活动少,致减少光照从而引起VitD减少。且肥胖儿童的不良饮食习惯可减少VitD的摄入。本研究中,肥胖 (-) 儿童中,OSA (+) 儿童25(OH) D水平明显低于OSA (-) 儿童,差异有统计学意义。OSA (+) 儿童中,肥胖 (+) 儿童与肥胖 (-) 儿童25(OH) D水平差异无统计学意义。排除了肥胖对血清25(OH) D测定的干扰。

近年的研究显示,OSAHS存在着全身炎症反应[25],低水平VitD与全身炎症反应密切相关。Th1细胞主要介导细胞免疫,分泌细胞因子INF-γ、IL-2以及肿瘤坏死因子α(TNF-α);Th2细胞主要介导体液免疫,分泌细胞因子IL-4和IL-5。IFN-γ可增强25(OH) D3-1α-羟化酶的活性, 增加活性VitD的产生,从而加强杀菌作用,IL-4通过增强VitD-24羟化酶的活性, 减少活性VitD的产生,从而减弱杀菌作用。VitD能使T细胞增加向Th2细胞转化,限制向Th1细胞转化,减少Th1细胞相关的细胞因子的产生,增加Th2细胞IL-4的分泌[26],防止免疫反应过程中对组织造成伤害。低水平的VitD导致Th1转化增多,Th1/Th2平衡紊乱有助于促炎环境的产生,并可以促进组织破坏,导致人类疾病[27],如慢性鼻炎。

OSAHS患者的血液中存在着多种生物标记物的升高[28],如:C反应蛋白 (CRP)、IL-6和TNF-α等。TNF-α可以促睡眠, VitD可以抑制淋巴细胞增殖、分化及转录因子 (nuclear factor kappa B, NFκB) 的激活[29],减少细胞因子 (IL-1、IL-2、TNF-α) 的分泌。由VitD降低引起的慢性鼻炎、扁桃体肥大、肥胖及较差的肌肉骨骼功能等,这些均增加OSAHS发生的风险。

我们对OSAHS组25(OH) D水平与LSaO2、AHI及Conners父母症状问卷、血脂指标的相关性进行研究,发现25(OH) D水平与焦虑呈正相关,与LSaO2、AHI及品行问题、学习问题、心身障碍、冲动-多动、多动指数、TG、TC、HDL-C、LDL-C无明显相关。

Pan等[30]实验发现孕期维生素D缺乏对大鼠后代心理及行为有明显负性影响,尤其是儿童期,可导致焦虑情绪增加,与本研究结果一致。这可能与儿童期神经系统对维生素D缺乏更敏感,维生素D缺乏致多巴胺能系统功能发生异常有关。25(OH) D水平与AHI及血脂指标的关系目前仍无明确结论,Kerley等[31]认为VitD水平与AHI呈负相关,Kheirandish-Gozal等[32]认为25(OH) D与LSaO2呈正相关;Barcelo等[33]认为25(OH) D与AHI不存在相关性,Esteitie等[34]认为25(OH) D与LSaO2无明显相关性,Jorde等[35]对VitD和血脂的横断面研究中未得出一致结论。Kheirandish-Gozal等[32]认为25(OH) D与TC、TG、HDL-C、LDL-C无相关性。这些与本研究一致,这可能是由于本研究样本量较少,因此多中心、大样本的后续研究有必要进行。故不能将血清25(OH) D水平作为评价儿童OSAHS严重程度及行为认知异常的指标。

我们的研究结果表明,VitD水平在OSAHS儿童体内明显降低,这对进一步了解OSAHS儿童的病理生理改变有一定的临床意义。VitD水平降低的儿童可能存在夜间低氧血症及焦虑,影响儿童的睡眠及心身发育。但VitD并不能反映夜间睡眠打鼾严重程度,在临床工作中需要结合睡眠监测数据及临床检查对此类儿童进行恰当的治疗。

| [1] | O'Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, et al. Neurobehavioral correlates of sleep-disordered breathing in children[J]. J Sleep Res, 2004, 13(2): 165–172. DOI:10.1111/jsr.2004.13.issue-2 |

| [2] | Lagishetty V, Liu NQ, Hewison M. Vitamin D metabolism and innate immunity[J]. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2011, 347(1-2): 97–105. DOI:10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.015 |

| [3] | Aydin S, Aslan I, Yildiz I, et al. Vitamin D levels in children with recurrent tonsillitis[J]. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2011, 75(3): 364–367. DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.12.006 |

| [4] | Reid D, Morton R, Salkeld L, et al. Vitamin D and tonsil disease-preliminary observations[J]. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2011, 75(2): 261–264. DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.012 |

| [5] | Pinto JM, Schneider J, Perez R, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are lower in urban African American subjects with chronic rhinosinusitis[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2008, 122(2): 415–417. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.038 |

| [6] | Mccarty MF, Thomas CA. PTH excess may promote weight gain by impeding catecholamine-induced lipolysis-implications for the impact of calcium, vitamin D, and alcohol on body weight[J]. Med Hypotheses, 2003, 61(5-6): 535–542. DOI:10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00227-5 |

| [7] | Erden ES, Genc S, Motor S, et al. Investigation of serum bisphenol A, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome[J]. Endocrine, 2014, 45(2): 311–318. DOI:10.1007/s12020-013-0022-z |

| [8] | Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition:highlights and modifications[J]. Chest, 2014, 146(5): 1387–1394. DOI:10.1378/chest.14-0970 |

| [9] | 中华耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志编委会, 中华医学会耳鼻咽喉科学分会. 儿童阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停低通气综合征诊疗指南草案 (乌鲁木齐)[J]. 中华耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志, 2007, 42(2): 83–84. |

| [10] | Hossein-Nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin D for health: a global perspective[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2013, 88(7): 720–755. DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.05.011 |

| [11] | 沈晓明, 王卫平. 儿科学[M]. 7版: 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2004: 75-77. |

| [12] | Jorde R, Grimnes G. Vitamin D and metabolic health with special reference to the effect of vitamin D on serum lipids[J]. Prog Lipid Res, 2011, 50(4): 303–312. DOI:10.1016/j.plipres.2011.05.001 |

| [13] | Hawes JE, Tesic D, Whitehouse AJ, et al. Maternal vitamin D deficiency alters fetal brain development in the BALB/c mouse[J]. Behav Brain Res, 2015, 286: 192–200. DOI:10.1016/j.bbr.2015.03.008 |

| [14] | Pan P, Jin DH, Chatterjee-Chakraborty M, et al. The effects of vitamin D (3) during pregnancy and lactation on offspring physiology and behavior in sprague-dawley rats[J]. Dev Psychobiol, 2014, 56(1): 12–22. DOI:10.1002/dev.v56.1 |

| [15] | Yin L, Grandi N, Raum E, et al. Meta-analysis: longitudinal studies of serum vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009, 30(2): 113–125. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04022.x |

| [16] | Salekzamani S, Neyestani TR, Alavi-Majd H, et al. Is vitamin D status a determining factor for metabolic syndrome? A case-control study[J]. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2011, 4: 205–212. |

| [17] | Gominak SC, Stumpf WE. The world epidemic of sleep disorders is linked to vitamin D deficiency[J]. Med Hypotheses, 2012, 79(2): 132–135. DOI:10.1016/j.mehy.2012.03.031 |

| [18] | Cutolo M, Paolino S, Sulli A, et al. Vitamin D, steroid hormones, and autoimmunity[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2014, 1317: 39–46. DOI:10.1111/nyas.2014.1317.issue-1 |

| [19] | 牟林琳. 综述维生素D与免疫功能相关的临床疾病研究[J]. 中国中医药咨讯, 2011, 3(4): 37. |

| [20] | Wang LF, Lee CH, Chien CY, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are lower in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis and are correlated with disease severity in Taiwanese patients[J]. Am J Rhinol Allergy, 2013, 27(6): e162–e165. DOI:10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3948 |

| [21] | Abuzeid WM, Akbar NA, Zacharek MA. Vitamin D and chronic rhinitis[J]. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2012, 12(1): 13–17. DOI:10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834eccdb |

| [22] | Camargo CJ, Ganmaa D, Frazier AL, et al. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation and risk of acute respiratory infection in Mongolia[J]. Pediatrics, 2012, 130(3): e561–e567. DOI:10.1542/peds.2011-3029 |

| [23] | Nunn JD, Katz DR, Barker S, et al. Regulation of human tonsillar T-cell proliferation by the active metabolite of vitamin D3[J]. Immunology, 1986, 59(4): 479–484. |

| [24] | Wood RJ. Vitamin D and adipogenesis: new molecular insights[J]. Nutr Rev, 2008, 66(1): 40–46. DOI:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.00004.x |

| [25] | Tauman R, Lavie L, Greenfeld M, et al. Oxidative stress in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome[J]. J Clin Sleep Med, 2014, 10(6): 677–681. |

| [26] | Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, et al. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3[J]. Blood, 2005, 106(10): 3490–3497. DOI:10.1182/blood-2005-05-2044 |

| [27] | Kamen DL, Tangpricha V. Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: modulation of innate and autoimmunity[J]. J Mol Med (Berl), 2010, 88(5): 441–450. DOI:10.1007/s00109-010-0590-9 |

| [28] | Kheirandish-Gozal L, Bhattacharjee R, Kim J, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells and vascular dysfunction in children with obstructive sleep apnea[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2010, 182(1): 92–97. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200912-1845OC |

| [29] | Suzuki Y, Ichiyama T, Ohsaki A, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D (3) in human coronary arterial endothelial cells: Implication for the treatment of Kawasaki disease[J]. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2009, 113(1-2): 134–138. DOI:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.12.004 |

| [30] | Pan P, Jin DH, Chatterjee-Chakraborty M, et al. The effects of vitamin D (3) during pregnancy and lactation on offspring physiology and behavior in sprague-dawley rats[J]. Dev Psychobiol, 2014, 56(1): 12–22. DOI:10.1002/dev.v56.1 |

| [31] | Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Bolger K, et al. Serum Vitamin D Is Significantly Inversely Associated with Disease Severity in Caucasian Adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome[J]. Sleep, 2016, 39(2): 293–300. DOI:10.5665/sleep.5430 |

| [32] | Kheirandish-Gozal L, Peris E, Gozal D. Vitamin D levels and obstructive sleep apnoea in children[J]. Sleep Med, 2014, 15(4): 459–463. DOI:10.1016/j.sleep.2013.12.009 |

| [33] | Barcelo A, Esquinas C, Pierola J, et al. Vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnea[J]. Respiration, 2013, 86(4): 295–301. DOI:10.1159/000342748 |

| [34] | Esteitie R, Naclerio RM, Baroody FM. Vitamin D levels in children undergoing adenotonsillectomies[J]. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2010, 74(9): 1075–1077. DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.06.009 |

| [35] | Jorde R, Grimnes G. Vitamin D and metabolic health with special reference to the effect of vitamin D on serum lipids[J]. Prog Lipid Res, 2011, 50(4): 303–312. DOI:10.1016/j.plipres.2011.05.001 |

2017, Vol. 31

2017, Vol. 31